4,171 miles long, the largest drainage basin in the world, draining 40% of South America (2,720,000 square miles), 20% of the world’s river flow, 20% of the fresh water entering the world’s oceans, sending a plume of fresh water 62-124 miles wide, out 250 miles into the Atlantic Ocean.

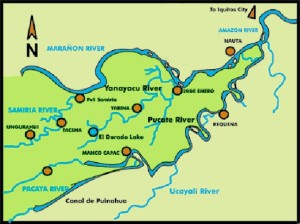

It starts as a tiny stream falling off a cliff in Ariquipa, Peru, high in the Andes, marked only by a wooden cross. It gathers force from other tributaries, crosses a flood plane, becomes the Maracon river, and joins with the Ucayali to become what we call the Amazon. It was named by Francisco de Orellana, Pizarro’s second in command, after he and his men were attacked by female warriors who clubbed to death anyone who couldn’t keep up with his retreat. Pizarro and company eventually made their way to the mouth of the river in 1547.

It starts as a tiny stream falling off a cliff in Ariquipa, Peru, high in the Andes, marked only by a wooden cross. It gathers force from other tributaries, crosses a flood plane, becomes the Maracon river, and joins with the Ucayali to become what we call the Amazon. It was named by Francisco de Orellana, Pizarro’s second in command, after he and his men were attacked by female warriors who clubbed to death anyone who couldn’t keep up with his retreat. Pizarro and company eventually made their way to the mouth of the river in 1547.

It rises and falls 30 meters from the wet to the dry seasons. The flooded forests on its banks (varzea) expand from 42,000 sq.miles to 140,000 sq.  miles, and with them the river’s width from 1- 6.2 miles to 30+ miles. We are there about mid-way through this process. The water lines on the trees are a vivid marker of high water.

miles, and with them the river’s width from 1- 6.2 miles to 30+ miles. We are there about mid-way through this process. The water lines on the trees are a vivid marker of high water.

There are so many more statistics – the most bio-diverse place on earth, for example, but you get the picture.

We will be spending our precious days navigating the Papaya-Samira Reserve –  the most intact area of the upper Amazon.

the most intact area of the upper Amazon.

We’ve been advised to bring bug-resistant clothes and insect repellant, and expect temps in the 90’s. We brought nets to go over our wide brimmed hats to ward off the expected swarms of malaria-carrying mosquitoes (of course we’re taking anti-malaria meds). Our expedition leader just smiles at our fears. “The Amazon has a bad rep,” he says. In fact, we encounter few mosquitoes, and the temperature is never unpleasant. At the end of the expedition, we’ll leave pounds of supplies on board, hoping someone will benefit.

The Delphin II travels through the night and I lie in bed, too excited to sleep, listening to its engines throb. There is just enough light to see the silhouettes of the jungle passing by our window wall.

We’re not in Kansas anymore.

What a thrilling adventure!

More to come, Stephen.